Inclusion Makers: DE&I Governance in Italy, in collaboration with Università Cattolica

Translation of “Inclusion Makers. La Governance DE&I in Italia in collaborazione con Università Cattolica” on HBR Italia by Shata Diallo and Maurizio Castagna

It only takes minimal exposure to organizations and communication campaigns to understand that DE&I (Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion) is no longer just the icing on the cake, but a strategic lever essential for businesses today. Promoting sustainability and inclusion has positive effects on employee well-being and, as described in other articles in this collection, also enhances performance quality, innovation, and the company’s competitive advantage.

In this context, inclusive companies are pioneers of a new leap forward: transforming toward a new business concept based on sustainability, collaboration, and innovation. The goal is to make employees active participants in organizational life and create social value, becoming a model for designing future sustainable organizations (see Soler & Marcè, 2017).

Easy to say, but much harder to do. Especially because, while the question “how do we give minorities equal opportunities?” is widely debated in organizational and research settings (often without exhaustive answers), few ask, “how can we ensure people truly feel included, and that being included generates a real competitive advantage?”

So, we can add another critical element: “how can we achieve all this in Italy?” We tackled this question in collaboration with Università Cattolica and the Research Center for Community Development and Coexistence Processes (CERISVICO) led by Professor Caterina Gozzoli, who, along with her team, has been working for years on enhancing differences from a more systemic and less rhetorical perspective.

THE RESEARCH: VALUING DIFFERENCES IN THE WORKPLACE

The general aim of the research was to explore the Italian context and understand what drives companies to adopt DE&I strategies and actions (Gazzaroli et al., 2022; Gazzaroli et al., 2023).

To capture a complete and representative picture, we decided to compare two key themes:

- The choices companies make regarding policies, processes, roles, and tools related to DE&I. We conducted individual interviews with 50 professionals responsible for inclusion and valuing differences in their companies, including HR Managers or DE&I Officers. The key findings from these interviews were shared with company representatives during a dedicated event.

- Employees’ experiences of inclusivity in their workplace, collected through a questionnaire. A total of 15 companies participated, and 3,247 questionnaires were completed.

Gli obiettivi specifici della ricerca sono stati:

- Explore the representations and possibilities that companies associate with the theme of diversity in the Italian context

- Map the organizational variables that most support the valuing of diversity and inclusion to design targeted interventions

- Identify best practices for valuing diversity to promote dialogue among various stakeholders

To ensure a consistent and useful interpretation of the data in line with organizational functioning mechanisms, the research team was supported by a Scientific Committee composed of Professor Gozzoli and Dr. Diletta Gazzaroli, the Mida Inclusion Team, and an Inclusion Advisory Board formed by 9 managers from large companies particularly sensitive to inclusion topics.

We aimed to challenge the traditional perspectives that view DE&I as merely the sum of small initiatives targeting marginalized groups, promoting instead a vision of inclusion grounded in the development of cultural change processes: pervasive, systemic, and rooted in organizational functioning mechanisms.

For this reason, in identifying the areas of investigation and designing the tools, we referred to a model that views inclusion processes from a more systemic perspective, the “organizational cultures of difference” (Podsiadlowski et al., 2012).

The model examines how a specific organization manages diversity on cultural and value levels, considering five levels of organizational maturity:

- Homogeneity: organizational cultures where differences are avoided or rejected, and the perception of similarity ensures effective working relationships

- Color blind: organizational cultures that respond to the idea of “we don’t see differences; there’s no need to talk about them because we are all the same”

- Fairness: organizations committed to ensuring fair treatment, but also just and responsive to different needs in support of minorities

- Access: organizations that view diversity as a business strategy to access different market segments

- Inclusion: companies where diversity is seen as a resource from which not only the organization, but each individual, can benefit and gain advantages

Alongside the model, we analyzed several variables related to the quality of work life to better understand the organizational cultures of difference present in Italy and to assess their impact on employees’ daily experiences. These variables included space for innovation, conflict culture, relationships with management, and commitment to the company.

HOW ARE WE ADDRESSING INCLUSION IN ITALY?

Let’s start with the conclusion: companies are addressing it, and they are doing so with commitment and seriousness, but there is still a long way to go.

The research findings stem from a combination of statistical analysis and critical review, with the involvement of a multidisciplinary team throughout all phases of the project. This team consisted of professionals from academia, consultancy, and the corporate world. From this critical analysis, several key areas for improvement have emerged.

ON DIVERSITY, THERE IS A NEED FOR (A LOT OF) TRAINING

People express curiosity about interacting with diverse individuals and perspectives. This is clearly demonstrated by the results of the semantic differential, which explored employees’ experiences starting from two opposing statements (see figure 1).

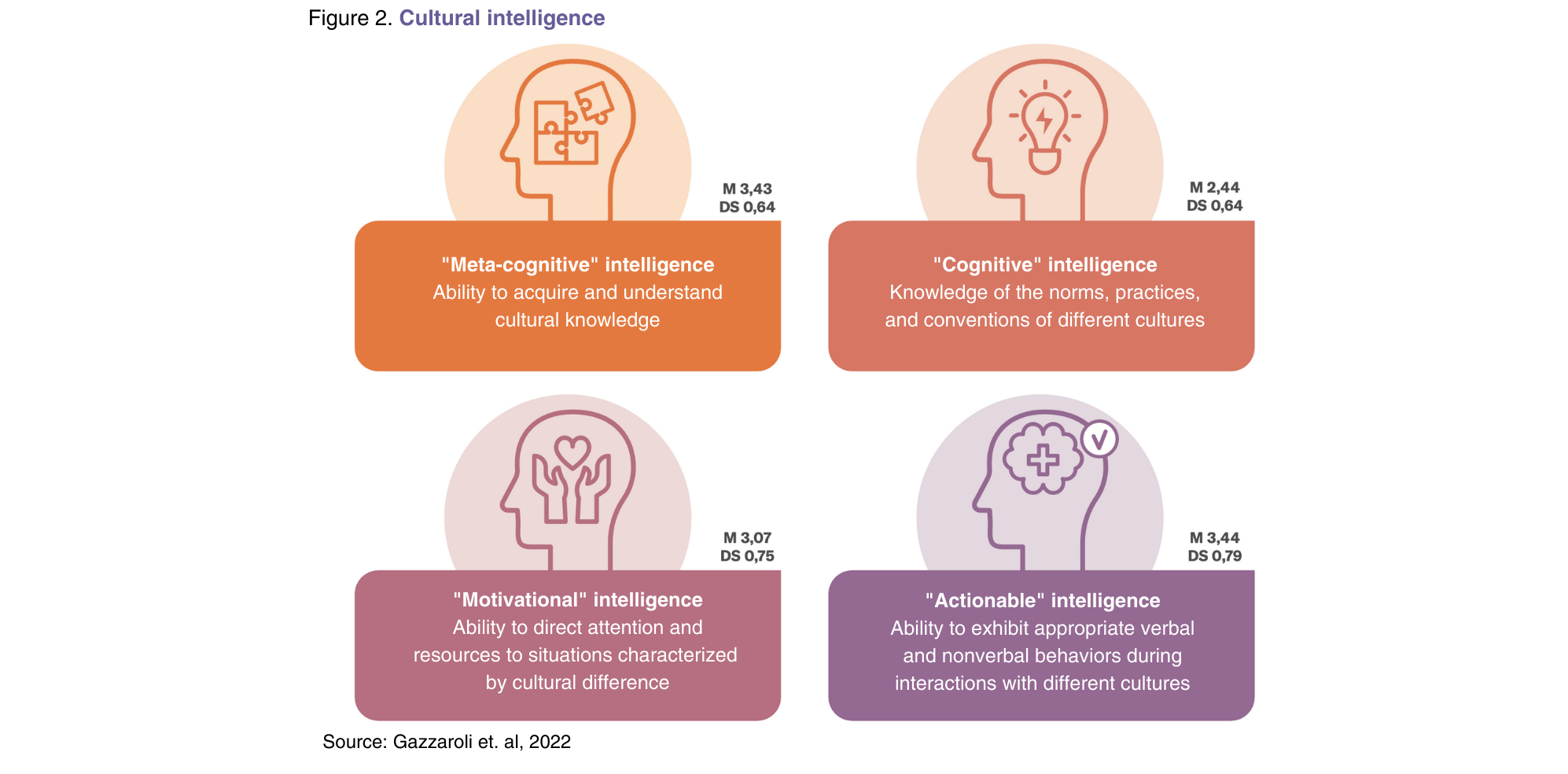

The fact that the average responses mostly fall in the center of the graph is actually a positive sign: it indicates curiosity and an awareness that diversity is complex and challenging. However, when it comes to equipping themselves with the right tools, the perception is akin to “walking on eggshells.” This is highlighted by the results of the Cultural Intelligence scale, which measures the perceived ability to understand, act, and effectively manage culturally diverse environments. Medium-to-low scores in this case reveal that people do not feel very competent.

Regardless of gender or age, people recognize the value of diversity and are aware that engaging with it can offer personal and professional growth opportunities. Yet, lacking the skills and tools to manage this diversity, people find themselves unable to seize that opportunity, remaining in a “static” state that is not very constructive or innovative (see figures 2 and ).

ITALIAN ORGANIZATIONAL CULTURES ARE STILL TOO HOMOGENEOUS

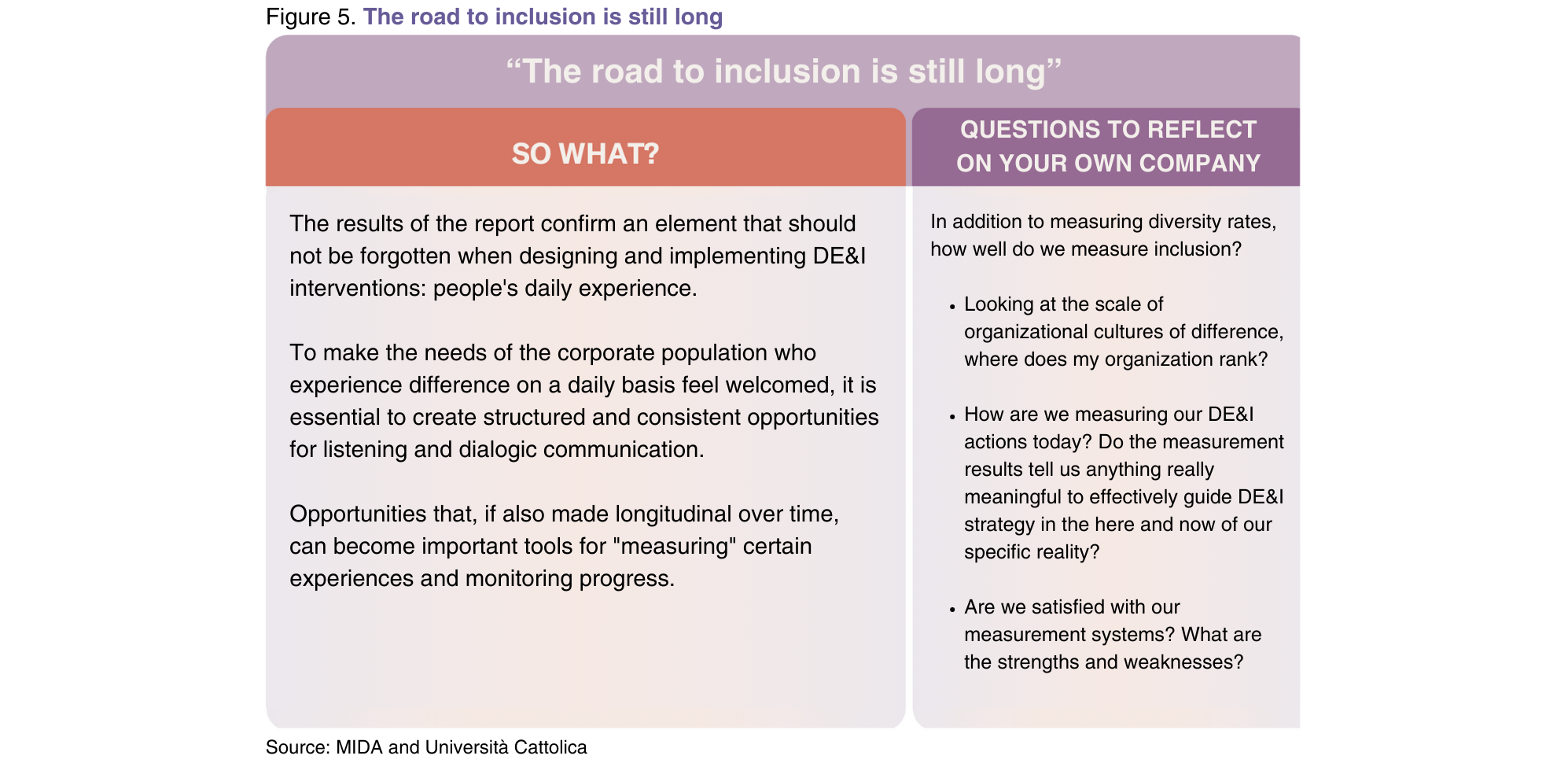

Asking people directly, “How included do you feel?” is one thing, but using validated scales that truly capture the complexity of organizational culture yields a less encouraging result.

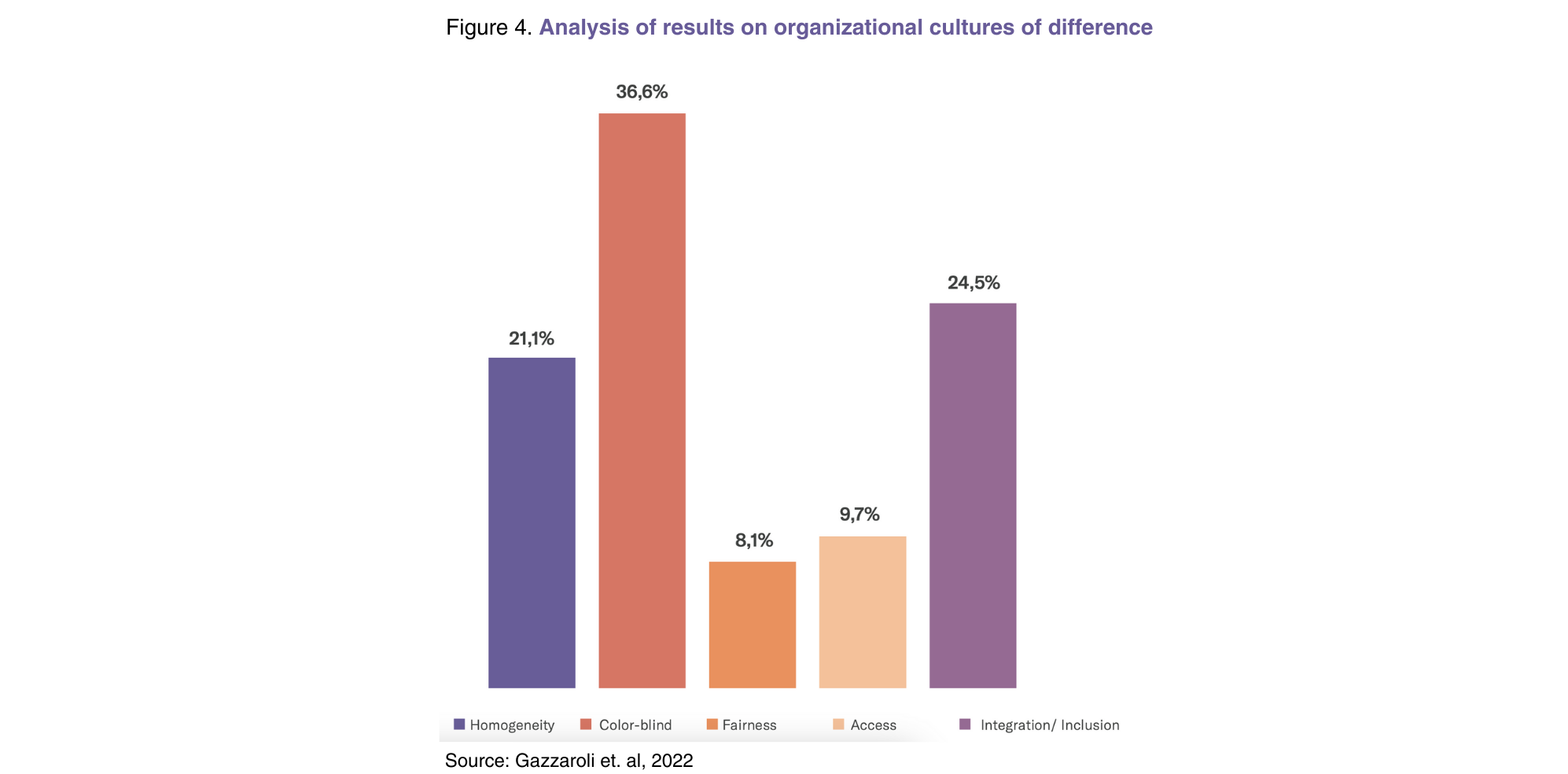

More than 50% of the sample feels they belong to a culture of homogeneity (where differences are avoided or rejected, and perceived similarity ensures effective working relationships) or color-blindness (where workers believe everyone should be treated equally) (see figures 4 and 5).

HOMOGENEITY OF PERCEPTION ACROSS GENDERS AND GENERATIONS

Across various scales and 220 items, there were no statistically significant differences related to gender or generation. In other words, the perception of inclusion or exclusion is the same for women and men, junior and senior employees (see figure 6). Moreover, the literature has long shown that categorization—such as by gender—reinforces the perception of difference and strengthens resistance to change (Zanoni & Janssens, 2007).

SHOULD DE&I PROFESSIONALS FOCUS SOLELY ON TRAINING?

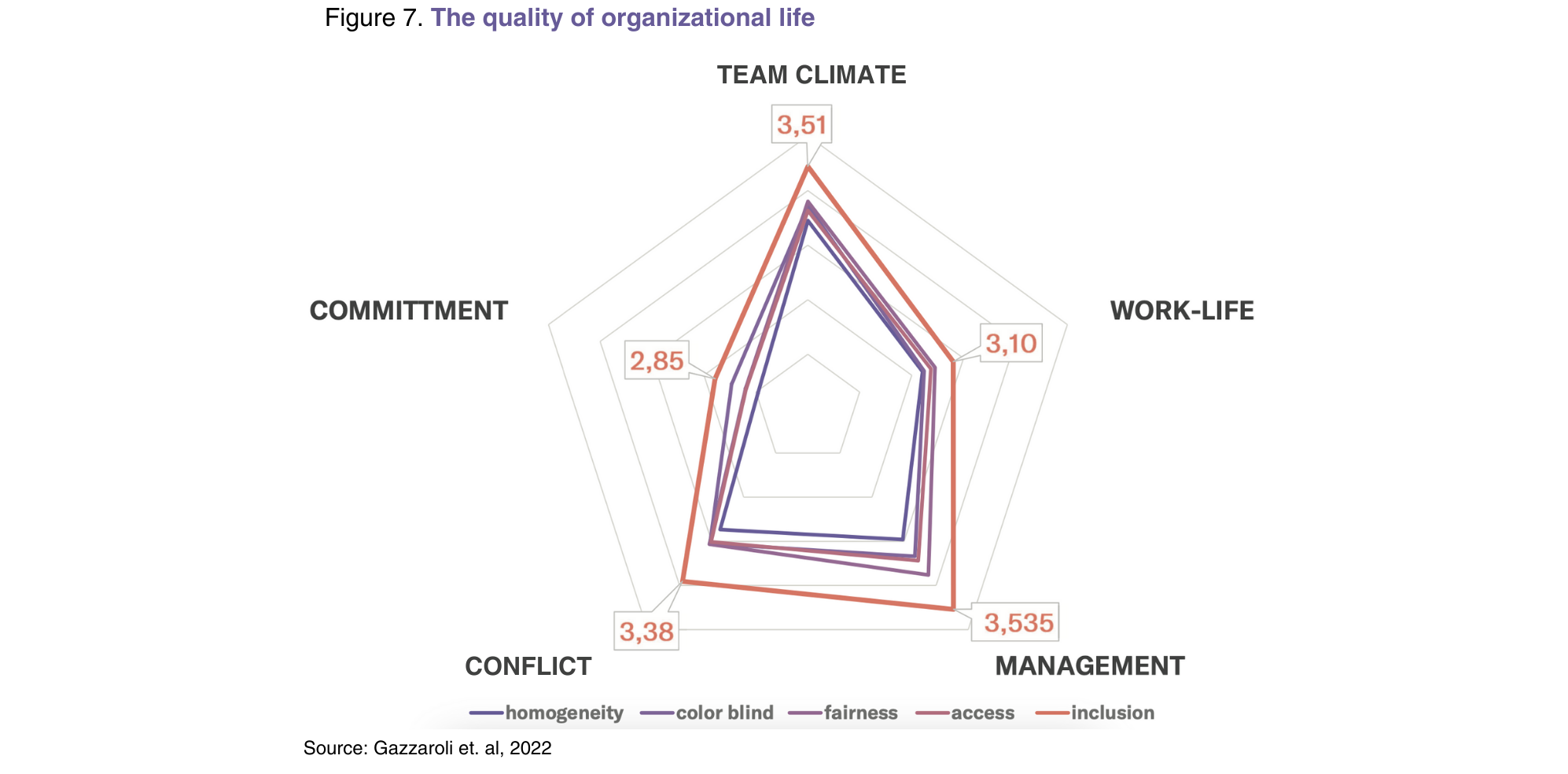

The study reveals that those who feel they belong to a truly inclusive organizational culture score significantly higher in all areas impacting the quality of organizational life.

Team climate, commitment to the company, relationships with management, growth opportunities, psychological safety, and the perception of being able to influence decisions: in all these areas, people who feel included are happier, enjoy their work more, and believe in it more.

This confirms, on one hand, the great importance of a truly inclusive approach, and on the other, suggests that addressing inclusion means placing importance on interventions that also impact other organizational levers (see figure 7).

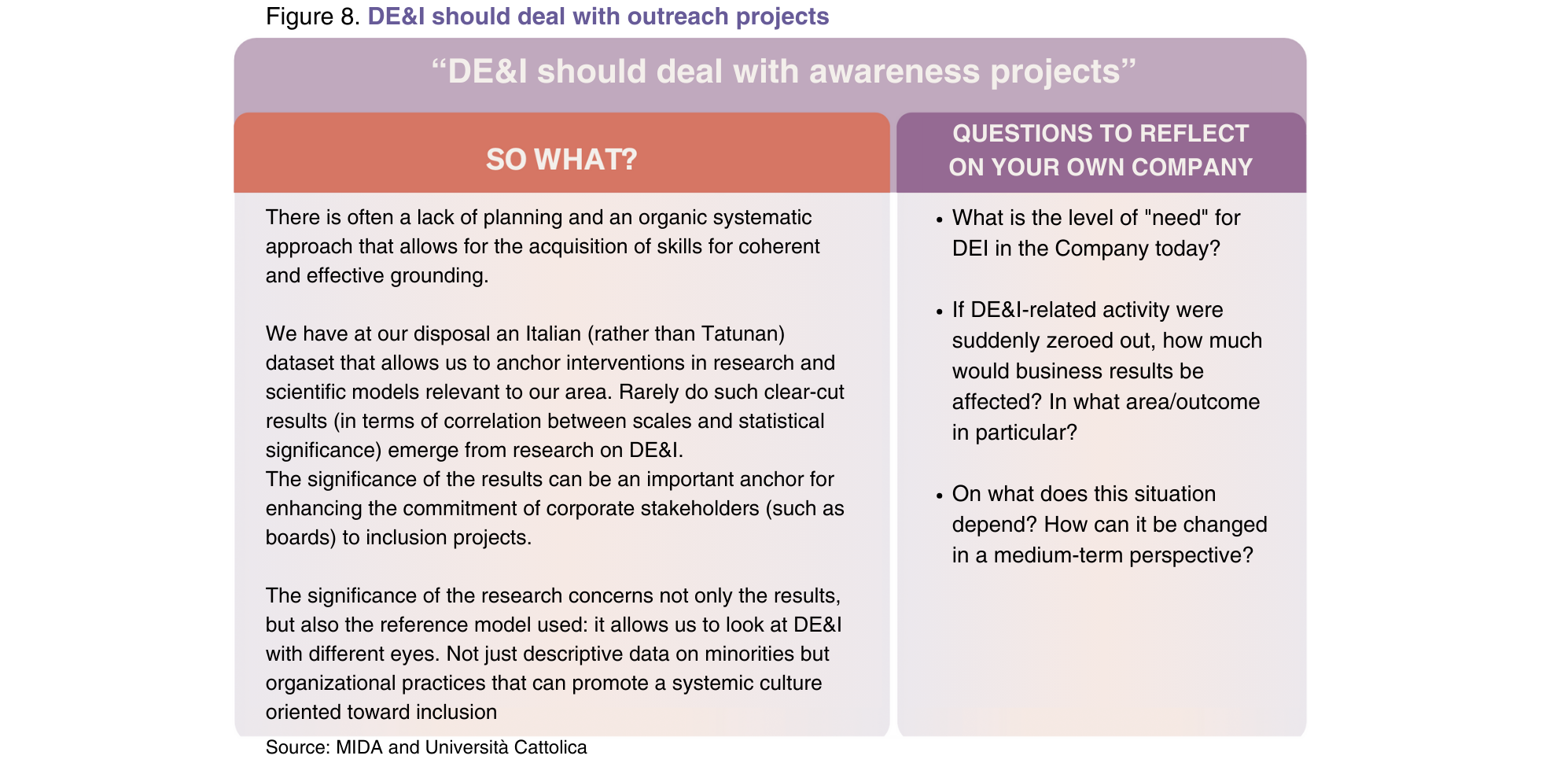

Often, companies implement significant initiatives that are deeply felt, but they run “parallel” to business and people strategies. What emerges as crucial, however, is that various initiatives should be synergistic, and those responsible for DE&I must take on not only training but also other complementary and synergistic interventions (see figure 8).

FOCUSING ON DIFFERENCE OR INCLUSION?

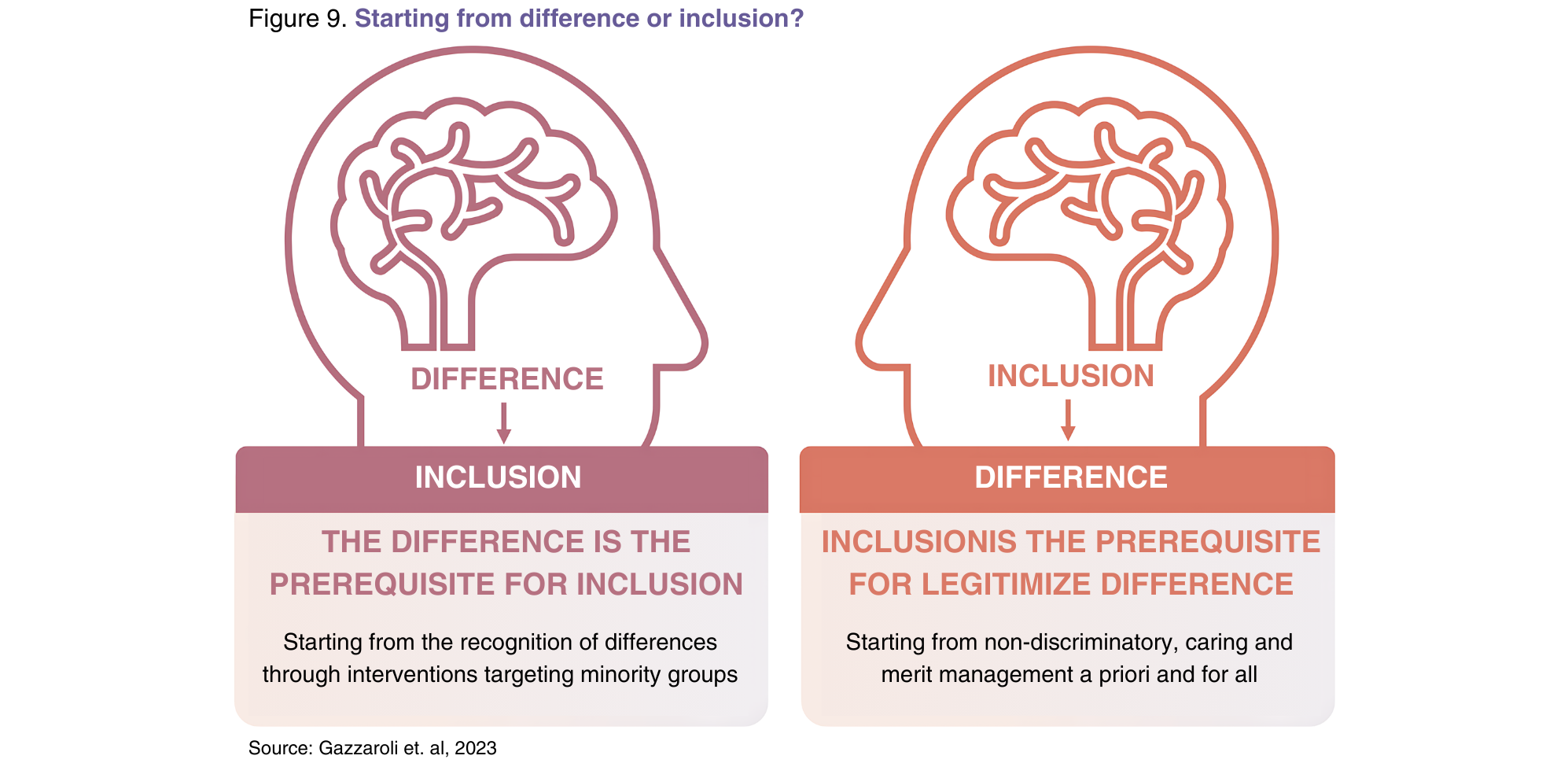

The interviews with management revealed two distinct and opposing perspectives. Some start with difference, focusing on groups at risk of marginalization, while others start with inclusion of everyone, aiming to value the excluded in this way (see figure 9).

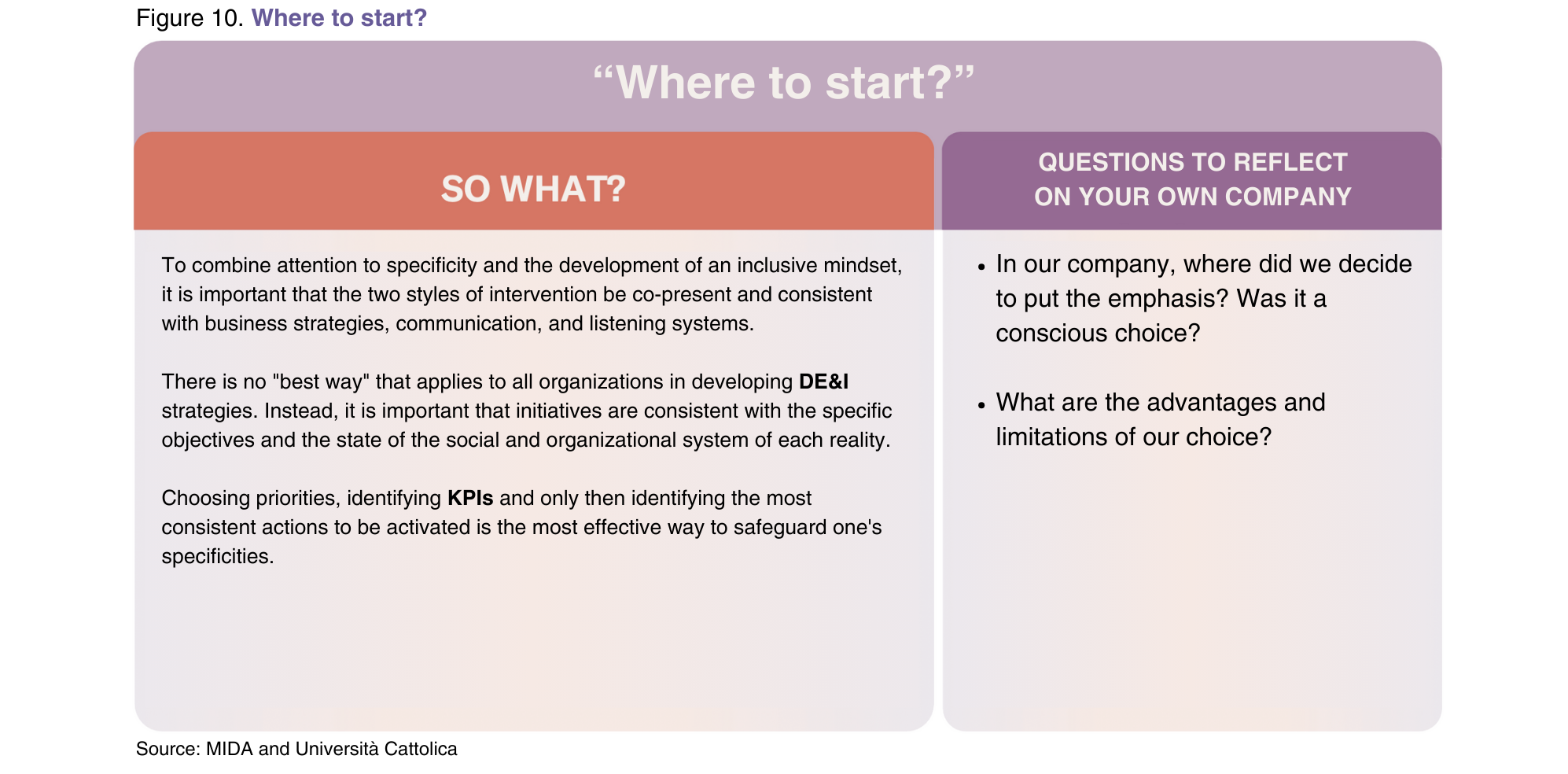

There is no magic formula, and both positions carry areas of risk. Starting from difference often carries the narrative of “I, the company, with strong power, give you, with weak power, the opportunity to access and grow.” This narrative reflects a power imbalance that might, in the eyes of employees, heighten the perception of a gap between groups and reinforce resistance to change.

On the other hand, starting from inclusion sometimes leads to the narrative of “we don’t focus on diversity because we’re all the same.” Working across the entire workforce without distinction can weaken systems for addressing individual needs and unique traits, failing to acknowledge the challenges that come with valuing difference (see figure 10).

The approach chosen by the company, in both cases, significantly influences its DE&I strategies and actions.

NOT JUST HR

Among the 50 professionals interviewed, the majority are from HR (and women). Positioning this practice within human resources brings advantages, such as the operational capacity to quickly reach people, but it also has its limitations. In recent years, the idea that DE&I is primarily, if not exclusively, an HR issue has taken root. This has led to a lack of accountability from other functions and departments (see figures 11 and 12).

TRAINING IS ESSENTIAL BUT NOT ENOUGH

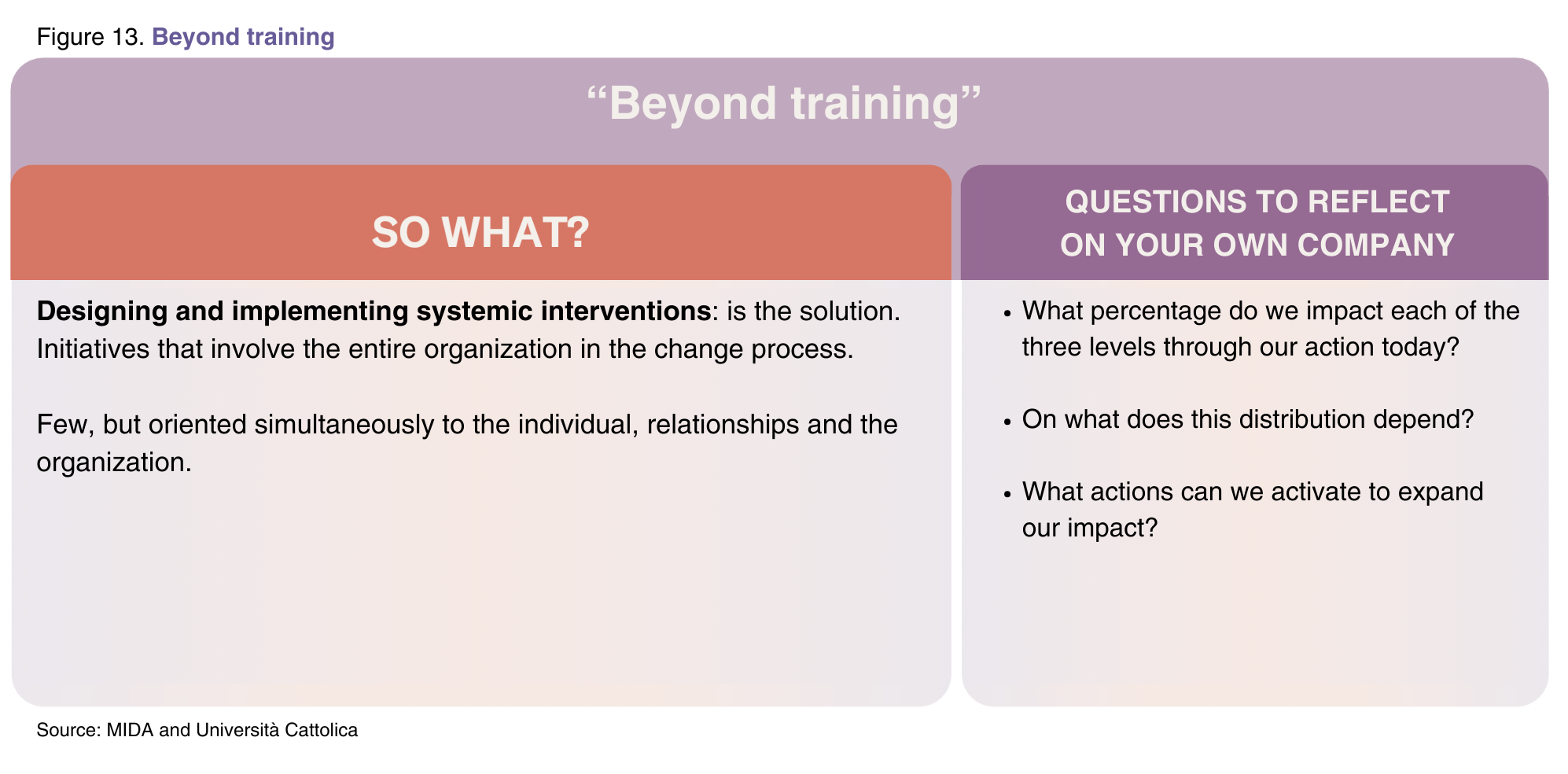

Training is important, but according to those working in DE&I, it is not sufficient on its own.

Yet, the vast majority of interventions in companies focus on the individual level: training as if it’s the only solution to achieve cultural change. Without a doubt, it is one of the easiest levers to activate, but it’s not the only one (see figure 13).

The research highlighted three indispensable and strongly interconnected levels:

- Individual, linked to the development of widespread awareness about DE&I

- Relational, connected to managerial styles and interpersonal and team relationships

- Organizational, related to the review of practices, processes, and policies

“To achieve global and lasting results,” companies say, “it is necessary to act on all three levels.”

COMBINING THEORY AND PRACTICE: THE CHALLENGE OF MIDA AND UNIVERSITÀ CATTOLICA

Interview with Caterina Gozzoli

Caterina Gozzoli, Full Professor of Work and Organizational Psychology at the Faculty of Psychology, is a professor of Clinical Psychology of Groups and Organizations, and Social and Organizational Coexistence. She is also the Scientific Director of the Advanced Training Program “Diversity & Inclusion Makers Executive Program”.