Why Focus on Inclusion Management rather than Diversity Management?

Services

Translation of “Perché fare inclusion management e non diversity management?” on HBR Italia by Elisa Rando e Sara Reggiani

In recent years, many organizations have started to focus on Diversity and Inclusion. From our privileged position as a consulting firm, we observe that organizations approach the topic with very different objectives, targets, and intervention methods: some companies carry out numerous initiatives to promote more inclusion and equity for specific targets (women, people with disabilities, LGBTQI+ people, etc.); others incorporate the theme into their business strategies and employer branding, without dedicated structures to implement them; and still others plan interventions based on very strict quantitative KPIs, to name a few examples.

A question we are often asked is: “Despite all our efforts to increase and value diversity and create inclusion in our organizations, why does it seem like there is still a long way to go before we can truly call them inclusive workplaces?”

To answer this question, inspired by the Peoplecology principle of simplification, we need to start from the beginning and the psycho-social meaning of Diversity and Inclusion. The literature does not offer a clear consensus when it comes to defining Diversity and Inclusion, but there are recurring and more or less widely accepted guidelines.

DIVERSITY

Diversity refers to the variety within our human species and concerns the heterogeneity of the demographic composition of groups and organizations (see figure). It is a concept used to identify:

- Individual characteristics of people: age, gender, background, experiences, perspectives, knowledge, abilities, ideas, etc. It is important to clarify that these characteristics are often considered as “diversity” in relation to how present and/or recognized they are by a “majority group” (often seen as the “reference standard”).

- People belonging to a “non-dominant” group (referred to here as a “minority group”), historically with fewer privileges and less access to resources/opportunities/etc. From this perspective, we can say that diversity does not exist in isolation. What is considered different depends on the context, particularly on the “composition” of the majority group.

“Each of us should be encouraged to embrace our own diversity, to see our identity as the sum of our various affiliations, rather than confusing it with a single, supreme one, used as a tool of exclusion, and sometimes even as a tool of war.” (Maaluf, 1999)

#BEING

The collection of human differences and variations, both inherited (from birth) and acquired through experience, at risk of exclusion, unequal treatment, or discrimination.

Age and generation, gender and gender expression, sexual orientation, physical and mental ability, health status, personality traits and behaviors, race, ethnicity and religion, language and nationality, place of origin (e.g., rural or urban), social origin and family background, socio-economic status.

Source: MIDA

INCLUSION

Inclusion is probably one of the most debated definitions in academic literature, but a common thread ties all interpretations together: while diversity is a fact (intrinsically linked to human nature), inclusion is a strategy for action and a process of change (see figure).

#ACTING

Practices that make everyone feel welcome, valued, and respected.

Work conditions that ensure a sense of belonging and psychological safety.

Source: MIDA

Therefore, the concept of inclusion is much more complex than diversity. Studies in social, organizational, and cross-cultural psychology explore it through two parameters:

- Its dimensions, which answer the question: “What is Inclusion made of?”

- Its contextual characteristics, which answer the question: “Where should I look to find, generate, and measure Inclusion?”

Imagine creating a music playlist with a variety of songs. What we all want is for our playlist to have a certain coherence or musical theme that we enjoy, but at the same time, we want the songs to be diverse, each with its unique musical style and special characteristics that add variety and emotion. Finding this balance is important to make the playlist interesting and enjoyable. If all the songs were too similar and fit only one genre, the playlist might become boring and monotonous. On the other hand, if every song were completely different from the others, the playlist could feel chaotic and disorganized.

If we were to create a good playlist inspired by the Optimal Distinctiveness Theory (Brewer, 1991), it would suggest balancing general coherence with song diversity. In other words, following a musical theme that defines the playlist while including diverse songs that are recognizable for their uniqueness within that theme. How can we apply this theory to organizational dynamics related to Inclusion?

The Optimal Distinctiveness Theory, proposed by social psychologist Marilynn Brewer in 1991, is based on previous research on social identity theory, social dilemmas, and evolutionary biology. The theory explains the psychological motivations that drive people to identify with groups, starting from the assumption that human beings have two fundamental and opposing needs: the need to belong to a group of similar individuals (belonging) and the need to feel unique or distinct within the group (uniqueness), just like in a playlist.

At the organizational level, we can explain these two needs as:

- The need for recognition and connection between the individual and the organization, not tied to individual characteristics, but to the contribution each person feels they can make within the organization and the extent to which this contribution is recognized by the system.

- The need for distinctiveness, or the desire to express one’s unique qualities (pursuing their full identity) while continuing to feel part of the group/organization.

We can therefore speak of inclusion in an organizational context only when the sense of contribution and belonging is combined with the appreciation of individual uniqueness.

INCLUSION AS A “MULTI-LEVEL EXPERIENCE”

If Belonging and Uniqueness are the dimensions of inclusion, what contextual characteristics can foster these dimensions?

When referring to contextual characteristics, two common perspectives emerge:

- Inclusion is a psychological state, an individual perception. The context that fosters this perception is one where people feel they can freely express themselves, openly share their opinions—even if they differ from the majority—and adapt their growth path to their own ambitions and aspirations.

- Inclusion is linked to organizational processes. Inclusive policies and practices can be embedded in most, if not all, organizational systems, including recruitment, selection, performance management, and compensation policies. They can influence decision-making processes, leadership and people management styles, and how the organization interacts with the surrounding community and stakeholders.

To observe inclusion/exclusion dynamics, generate and regenerate inclusion within and among groups, and measure the impact of initiatives and the long-term effects of inclusion-related goals, it is essential to focus on both of these characteristics.

The “Working Together” approach of Peoplecology highlights that inclusion cannot and should not be solely an individual responsibility, nor can it be entirely delegated to organizational functioning and management style. Inclusion brings life to organizational contexts; it is not a static process that stops once a goal is reached. Rather, it is a dynamic and ongoing process that is continuously shaped and reshaped by the interaction between people and their environment.

With these premises in mind, what does it mean to focus on Inclusion management, and why is it more effective and advantageous than Diversity management?

THE PATH TOWARD INCLUSION

Cross-cultural psychology studies tell us that “managing diversity” often involves processes of assimilation and integration— essentially offering minority groups the same opportunities and conditions as the majority group. For example, bringing in very young employees to stimulate innovative and creative approaches, without reconsidering or challenging the pre-existing mechanisms governed by senior employees.

This process, while often motivated by good intentions to provide greater opportunities to minority groups, has two potential consequences:

- It tends to further highlight the perception of difference, especially for those experiencing this assimilation or integration.

- It can also generate resentment within the majority group, who may feel that they are “losing fairness” and their “just rights.”

Let’s take another common organizational example: gender quotas, a form of “positive discrimination,” are an initiative of diversity management. Quotas give people from the less represented gender (typically women, making them the minority group in this case) a dedicated position to provide them with more opportunities than the more represented gender (usually men). This often creates a feeling among women that they were selected or promoted because of their gender rather than their competence and suitability. Meanwhile, men may feel a sense of “injustice” and a lack of equity in their favor.

Affirmative action is a political tool originating in Anglo-Saxon countries that aims to promote the participation of people with ethnic, gender, sexual, and social identities, among others, in contexts where they are minorities and/or underrepresented.

Operating within an Inclusion Management framework means going beyond the characteristics of majority and minority groups by establishing organizational enablers that facilitate dialogue between teams and individuals around shared goals. It also involves developing personal awareness and skills to support this dialogue effectively.

TRANSFORMING COMPANIES INTO TRULY INCLUSIVE WORKPLACES

Ecological thinking is more urbanistic than architectural, anchored in the understanding and respect of contexts. It is based on the awareness that even the most brilliant technological or organizational solutions cannot yield positive results for the company and its people unless they are connected to and harmonized with the specific organizational, cultural, and anthropological characteristics of the context.

Marco Poggi

To transform an organization into a more inclusive place, challenging and transforming processes and practices, it is essential to first help companies understand what inclusion means within their specific organizational context, connecting their internal characteristics to the elements we’ve discussed so far. This requires helping them assess “where they are today” and empowering them to choose their own priorities and define subsequent development and improvement actions in the direction of Inclusion Management.

Based on insights from the literature and the results of the research project “Valorizzare le differenze in azienda” conducted by MIDA in collaboration with the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, the Inclusion Strategy Compass model was developed. Its goal is to first diagnose the inclusivity of an organization’s processes, practices, and operational mechanisms, and then guide the creation of strategic plans aimed at Inclusion Management.

The major advantage of this model lies in the work process that accompanies it, as it brings two significant opportunities:

- Engaging not only HR but also Top Management, fostering awareness and involvement in the evolutionary importance of these issues for the organization.

- Connecting different and usually distant departments and functions (HR, Marketing, Communication, Audit, etc.), with a shared focus on implementing greater inclusivity in their processes.

THE MODEL AND WORK PROCESS

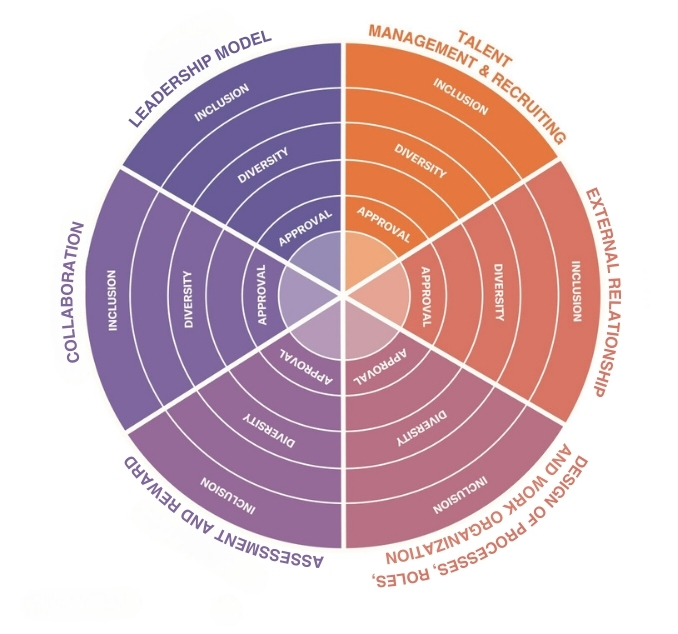

The Inclusion Strategy Compass is composed of:

- Three levels where an organization can be “positioned” based on its level of inclusivity (Approval, Diversity, Inclusion), developed from the studies of Podsiadlowski et al. (2012) on “Organizational Cultures of Difference.” These levels represent how organizations view difference, on a continuum ranging from “non-inclusive: we don’t seek difference” to “fully inclusive: we seek and value difference.”

- Six drivers on which the assessment is conducted, guiding the strategic plan to make the organization more inclusive (see figure).

Source: MIDA

With the INCLUSION STRATEGY COMPASS, we systematically analyze the processes present in the company, divided into 6 areas (drivers). For each driver, we determine the level of organizational maturity according to three levels:

• Approval Management: organizational models that are idealized, unifying, and homogenizing, considered rewarding based on individual characteristics.

• Diversity Management: companies aiming to increase their level of heterogeneity through the development of a series of actions and processes that enhance the presence of minorities within the system.

• Inclusion Management: companies focused on developing policies and practices that value differences and uniqueness to generate business impact and results.

The Inclusion Strategy Compass is a framework that allows us to take a comprehensive view of the entire company, synthesizing and systematizing existing processes and objectives (SDGs, ESG, etc.) with an inclusive perspective.

The three levels are characterized by different approaches to how the business system functions. This means that, in reality, organizations are unlikely to align with just one level; instead, they will likely present different configurations depending on the drivers observed and analyzed. The drivers of the Inclusion Strategy Compass indicate the “places” within an organization to “peek into” to understand whether it is moving toward Inclusion Management or not.

The research highlighted several HR processes that play a key role in determining an organization’s inclusivity (e.g., recruiting, development, etc.), as well as certain operational mechanisms that can promote a stronger sense of inclusivity.

From these findings, the model was built on the following six drivers:

- Talent management and recruitment

- Leadership model

- Design of processes, roles, and work organization

- Evaluation and reward systems

- Collaboration

- External relations

The drivers allow for the analysis of practices and processes using an assessment checklist that collects qualitative and quantitative data to provide a clear picture of the level of inclusivity. Having a clear snapshot of the evidence that places the drivers at different levels is often very effective. For example, the Leadership Model driver may be positioned at Inclusion Management, while the Talent Management and Recruitment driver might be at Approval, and so on.

The initial reaction to reviewing the data might be one of “there’s still a long way to go.” Fortunately, this feeling is often replaced in the following days by one of hope and excitement. From the evidence gathered, organizations select their work priorities (focusing on the drivers most important to their context), transform them into strategic objectives, and finally define an operational plan. This plan includes new initiatives, process reviews, identification of innovative practices, as well as KPIs for monitoring, identification of process owners, timelines for implementation, and more—all coherently aligned with the diagnosis and the specific characteristics of the context.

The very tangible feeling of being an active part of a strategic plan, of being able to truly make a difference, and contribute to the process of change toward a higher level of inclusion, makes the process exciting for all parties involved. It also increases the sense of responsibility in seizing the great opportunity to evolve one’s workplace with an inclusive perspective.

THE INCLUSION STRATEGIC PLAN FOR COOP LOMBARDIA

In March 2023, we launched a project with Coop Lombardia, a consumer cooperative operating in Italy’s organized retail sector. Coop Lombardia has over 780,000 members, a sales network of 88 stores (including hypermarkets and supermarkets), and about 4,500 employees across the region. In line with initiatives already implemented to enhance people and their career paths (e.g., the “Tu al centro” project) and in synergy with the ongoing efforts focused on equity and protecting specific sensitive groups, Coop Lombardia’s Human Resources Department decided to develop a strategic plan for inclusion.

In the first phase of the project, two types of analysis were chosen to provide a comprehensive picture of the current state of inclusion:

- Listening to employees through Focus Groups, aimed at investigating employees’ perceptions of inclusion during various stages of their employee experience.

- Organizational analysis of processes, policies, and business practices using the Inclusion Strategy Compass, to determine the maturity level of the system in terms of inclusion.

The results of this assessment allowed for the identification of very specific and coherent areas for intervention. What people expressed during the listening phase in the Focus Groups aligned closely with the findings from the organizational analysis.

The initial analysis revealed a cooperative strongly oriented toward diversity management, with certain areas leaning more toward Inclusion and others more toward Approval. This dual approach, analyzing both employees and the system, aligns with the literature that emphasizes the importance of looking at both contextual elements of inclusion (people’s perceptions and organizational enablers) to determine whether the observed context is inclusive and what needs to be addressed.

The first phase of the project, utilizing the Inclusion Strategy Compass and its checklist for collecting qualitative and quantitative data, received positive feedback. Particularly, in the interview given by Dr. Sara Cirincione, Head of Personnel, Selection, Development, and Equal Opportunities, she highlighted that, despite the initial perceived complexity of the model, the work process was simple, accessible, and effective. The added value came from the in-depth exploration of many small areas/mechanisms/practices to better understand the nuances of the organizational reality.

This allowed both the operational project team and the Top Management Steering Committee to realize concretely that, in many respects, the cooperative was already in a state of true inclusion (unsurprising given the cooperative’s inclusive nature). However, it also became clear—this time with some surprise—that in other areas, diversity alone “was not enough” and that a further step would be necessary to create real inclusion.

As a point of attention, Dr. Cirincione emphasized in her interview the need to accompany this model with as many listening moments as possible (just like the Focus Groups in the project). The risk, otherwise, is having a partial view of the situation.

The second phase of the project was dedicated to defining the Strategic Plan. This creative phase was highly engaging for the participants, allowing the project team and the Steering Committee to feel like the architects of future inclusion experiences at Coop Lombardia. “Starting with clear goals was essential,” said Dr. Cirincione. “Understanding exactly where we want to go, what we need to get there, and defining the actions to take, the timeline, and which KPIs to use is critical for addressing the identified needs and ensuring they don’t remain just promises on paper.”

Currently, Coop Lombardia is working on implementing the actions identified in the plan developed through the project. Two main aspects emerged from Dr. Cirincione’s feedback that encapsulate the spirit of Inclusion Management:

- The involvement of the entire organizational governance for real change. The engagement of the Cooperative’s management and top leadership, as well as the integrated work of the various departments and functions involved, ensured that this project was not just an “HR initiative” but instead had the full backing and attention of the entire organization. Everyone was aligned with the goals and outcomes of the project.

- The courage to self-reflect and decide to change. Without daring to look critically inward and confront areas for improvement without fear of judgment, it is impossible to initiate real change. This mindset—fully embraced by Coop Lombardia—leads to learning from successful initiatives and the many resources that have fostered inclusion, while also viewing areas for improvement as necessary challenges for the most important cause of all: ensuring the well-being and inclusion of their people.

THE POWER OF INCLUSION MANAGEMENT

Unlike Diversity Management practices, which are geared toward supporting specific categories at risk of marginalization, it has been demonstrated that Inclusion Management allows organizations to intervene by defining and redefining organizational enablers, mechanisms, tools, and devices that support the transformation process in an inclusive framework. Simultaneously, it activates listening and training processes centered on people, focusing on their perceptions and desires to feel included within the company.

Inclusion Management initiates a series of practices aligned with the very meaning of inclusion, which together generate the contextual dimensions necessary for inclusion to occur at all levels of the organizational ecosystem. These practices can ensure the necessary attention and structure over time to support and monitor the organization’s evolution process.